L3: How to prescribe them part 2

Pain-monitoring model1

In Silbernagel’s study one group (active rest) stopped running and jumping during the first six weeks of treatment (they were able to participate in other activities such as swimming, running in deep water using a buoyancy vest, riding or gentle walking). This is a common recommendation aimed at decreasing pain and inflammation by avoiding stretch shortening cycles (i.e. running and jumping). However, many athletes want to continue running. The other group in the study did just that using the pain-monitoring model. This model still involves reducing load initially but allows some within reason with a slow progression to return-to-sport. Both groups improved in terms of symptoms and muscle-tendon function.

A key feature of this exercise programme is the intensity of training involving daily exercises and a gradual increase of the load. This is believed to be beneficial because mechanical loading may be important in the healing process as well as improving strength of the tendon.7-9

It should be noted temporary active rest appears not to have significant long-term consequences and so it is safe to recommend short bouts of rest for those patients who you think would benefit. Moerch et al. found that two weeks of tendon load deprivation (in uninjured subjects) did not affect normal adaptive response to loading in the Achilles tendon compared with a loaded tendon.10 This is despite reductions in muscle size and strength being observed.11

Long-term unloading should be avoided as this is known to cause a decrease in collagen turnover and presumably does have an impact in terms of net loss of collagen.11-13

For the pain-monitoring model the following advice applies:

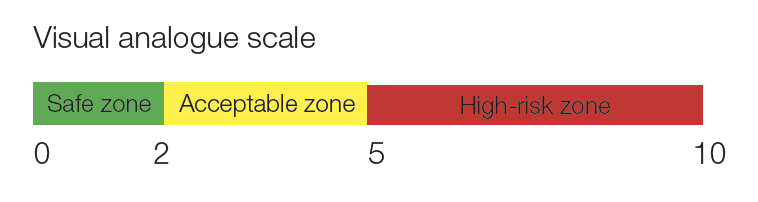

- The patient must not allow their pain to pass 5 on a visual analogue scale (0 is no pain, 10 is the worst pain imaginable) and the pain must subside by the following morning.

- Progress can be monitored using the visual analogue scale during one-legged hopping (see download).

- Pain and stiffness in the Achilles tendon is not allowed to increase from week to week.

As an example, if a patient reports three days of pain following a run and their pain is 6 out of 10 on a visual analogue scale following single leg hopping then that particular running routine is not recommended. If the patient was previously running 5 km reduce this to 2–3 km and ensure the recovery time is within 24 hours. On the rare occasion that the patient cannot run at all have them perform Achilles tendinopathy exercises until their pain is 3 or less on single leg hopping. Then when they start running again, start with low loads and gradually increase over time.

It could be useful to simultaneously prescribe exercises for gluteus medius and rectus femoris (see intermediate exercises for the gluteals and beginner quadriceps exercises for patellofemoral pain). In their study, Azevedo et al. found that “… relative muscle activity was significantly lower for tibialis anterior pre-heel strike, and rectus femoris and gluteus medius post-heel strike in the [Achilles tendinopathy] group. This shows differing muscle activation strategies at this crucial time in the gait cycle.”14 They commented “The reduction of knee range of motion in the injured group during the stance phase could reflect a weakness of the quadriceps during eccentric actions,15 and this is supported by the observation of lower integrated electromyographic activity of the rectus femoris during the stance phase observed in this group … The relationship between weak gluteus medius muscles and Achilles tendinopathy is not clear, but a weak gluteus muscle could result in adduction of the femur and internal rotation of the tibia, possibly increasing pronation.” Note that this type of training should not be a replacement for Achilles tendon and calf muscle training.